Product Management Webinar: Product Culture

Culture Clash: How to Make Product and Engineering Work Together Effectively

How can we build a great product and engineering culture?

Catch up on our webinar with David Subar, CTO, Chief Product Officer, founder, and managing partner of Interna, and host Janna Bastow, CEO of ProdPad and inventor of the Now/Next/Later roadmap to find out.

About David Subar

David Subar is a CTO, Chief Product Officer, and the founder and managing partner of Interna, a consultancy that enables technology companies to ship better products faster, to achieve product-market fit more quickly, and to deploy capital more efficiently. Interna has worked with companies ranging in size from small, six-member startups to the Walt Disney Company, and helped Pluto on the way to its $320MM sale to Paramount and Lynda.com on the path to its $1.5B sale to Linkedin.

Prior to founding Interna, David was CTO and CPO of a number of companies, including ZestFinance, Break Media, and Interthinx. He currently serves on the Board of Directors of the LA CTO Forum.

Key Takeaways

- Why product and engineering are so often out of alignment and how to fix it.

- Common evaluation metrics of each and why they are failing us.

- How to align your goals across product and engineering.

- Exploring the Spotify Product Development model.

[00:00:00] Janna Bastow: Hey, everybody. Welcome to ProdPad’s Product Expert Webinar. I’d like to introduce our guest. This is David Subar, and David is a CTO, a chief product officer, and he’s founder and managing partner of Interna.

David came on my radar through a colleague and I spotted one of his talks and it really resonated with me because it shone a new light on some of the exact problems that ended up talking to product customers about all the time. So I thought I’d invite them on here as this week product expert to share with you.

He’s going to be talking about how product and engineering teams just really commonly clash and why that is and what we can actually do with it.

[00:00:39] David Subar: Thank you. And thanks for having me. As Janna said, I’m going to talk today about the culture clash between product managers and engineering and how to make them work effectively together.

I started my career doing research and development in machine learning and artificial intelligence at a military owned think tank in Washington, DC. And we were working on problems about how do you determine what the enemy is doing? When the enemy is trying to not release information to you and start to release false information and using machine learning techniques, AI techniques, to try to figure that out.

And that sounds very exciting. And I was very excited frankly, to take the job, but what we were doing was not producing real products. What we were doing was research. And when you do research, you write a paper, that’s your own. And if it’s a good paper, maybe you presented a conference. Some of ours, we could, some of them, we couldn’t, because some were classified some weren’t and then maybe 200 people listened to you and then nothing else happens.

And so I started my career doing that, but I found it really frustrating because like I grew up a nerd, I wanted to use technology to build products that changed something that moved to market that mattered to someone that frankly, that I could tell my mom about and doing research, you just couldn’t do that.

And so from there I became an engineer, and then I took management roles, eventually becoming CTO of companies and then also running product. So I’ve had both product and technology roles. And what I spent time doing was thinking about how do you make these teams effective?

I went from building the product to building teams that build products, both product management and technology. It’s been a long time doing that. And then for seven years I’ve been doing at Turner, we consult with technology companies about product and engineering and how to make the teams more effective. And we evaluate teams and come with recommendations. We coach and mentor CTOs, chief product officers, engineering and technology executives. And we do interim roles. We will go and fix a team ourselves and come out, and doing that, we see a bunch of patterns among the companies, how product management and engineering work. So that’s, how I come to this. So I’m not gonna talk about one culture clash between product manager and engineering, but two: one between product manager and engineering, and one of that, that are both important.

And I’m gonna talk about five ways to overcome them. I encourage you, if you have questions to ask, please don’t hesitate to ask questions. So I’m going to start with what you need to overcome the culture clashes.

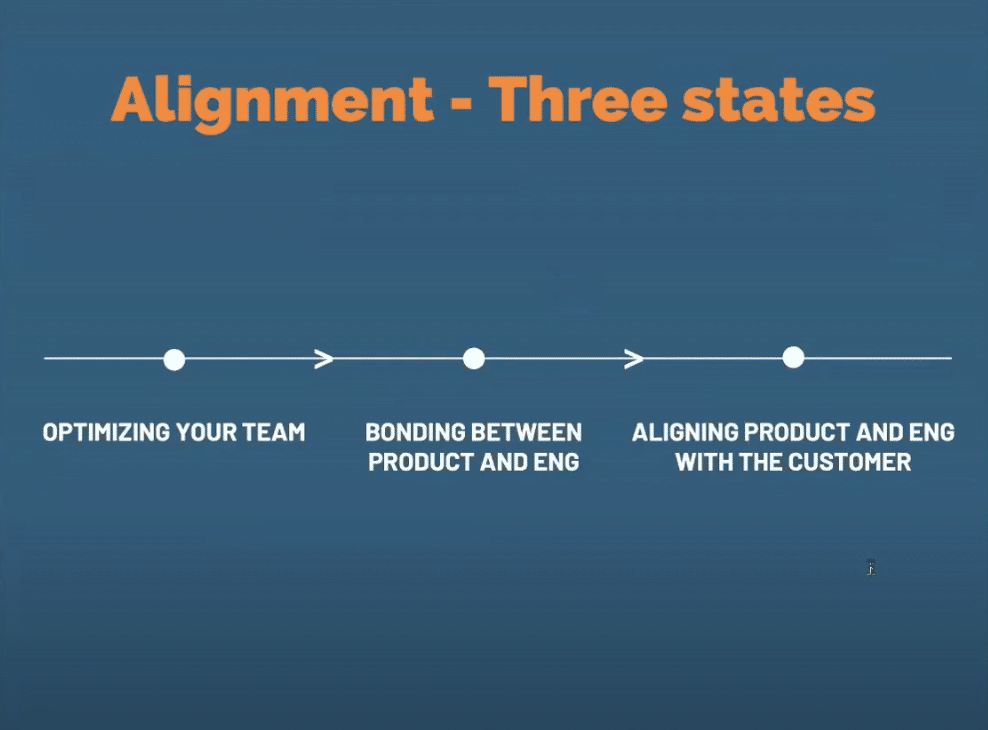

I’m going to dig into them, but there’s really five things that are important. Alignment, measurement, review, transparency, iteration. We’ll talk all about them, but first I want to talk about alignment now, and I’m talking alignment here initially between product manager and engineering, and there’s really three states of that.

So five things you need to know, three states of alignment, and we’re going to go into first optimizing the team. So here I use CTO, chief product officer, but really it could be any technology or product management executive using CTO and chief product officer as a shortcut. But a lot of people that run product teams, technology teams, spend time thinking about how to optimize their team’s efficiency.

I get some input, I do some process and I’ll output something. And I think about that’s what my team is responsible for. That’s what I have to make more efficient. So in product it might be: I collect some input from the markets, users, sales, marketing someone like that. I write some roadmap and some user stories.

And my output is that to engineering, to technology, and I’ve done my job and I want to do that better and more efficiently. And engineers often have a similar thought. I get some user stories. I write some code, I put it on servers and I’m done. I want to make that process more efficient. That’s well-meaning it’s thoughtful.

But this leads to the first culture clash that I want to talk about. Because if product management, if engineering’s primary concern is how I write code more efficiently, how I write better user stories. It creates a cancer in the organization. What happens when something goes wrong? And by the way, something will go wrong.

Something always goes wrong. There’s a question of, who’s to blame and engineering might often say if the product didn’t work the way users wanted it that’s not on me. That’s on my product manager. Or if we were late, those user stories weren’t really well-defined and they keep changing.

And so of course we can’t predict time. Or product might say if it’s late engineering predicted wrong, or if it’s buggy, QA and engineering didn’t think about it well, and what happens as much as when something goes wrong, then there’s a question of how do we change process to make this better?

And engineering might say, we need a lot more process upfront and we need you to find everything we can upfront so we can build a writer architecture and the right scalability or product might say we need better timelines. And so this goes from agile to waterfall. And, not only that, but we start putting up barriers between engineers and product.

And what I’m here to say is you need to think, but engineering with product is not two separate teams and not making those two independent groups to make them more efficient, but you need to think about them as one team. So that’s the reasonable next solution, is to think about product management, engineering as one team— bind them together.

And you see this a lot, right? This is a very agile concept. The three horsemen, so a product leader, an engineering leader, a QA leader, leading squads. And this is better, right? Because now the job is not to: I write software and put it on servers, or I write user stories.

Our job is to build a product, so great. That’s awesome. We’re moving forward, but it there’s another issue here is who are we moving forward for? Who is your customer? Who are we here serving? And oftentimes when I talk to people. When I go into companies, when I work with folks, oh, your product manager and engineering, you say, oh, we were here to do our customer sales.

Our customers marketing. The CEO has got a bunch of ideas. We just have to do what the CEO says, and my argument here is now you have the same culture clash. But instead of being between product management and engineering, it’s outside that moat. And I often get calls from CEOs at this point where CEOs or boards of directors, of bigger companies like Disney some executive might say, we keep putting more and more money into product managing and engineering and products aren’t getting out faster. They’re not better. This is a side effect of not understanding who you serve. I will hear this in the same conversations I’ll hear from the product management engineering group is we need to talk to business to find out what to do next. That’s another symptom of the same problem.

And when you hear that, you understand that there’s a moat between the product teams, product management, engineering, and the rest of the company. But the problem here is focusing on the wrong people, marketing and sales, the CEO, your CFO, they’re not your customer.

They can’t be your customer. They’re your teammates. You have to focus product management, engineering on who pays. Who do you really serve? Who does the company really serve? That’s the customer. Marketing and sales might have ideas of what needs to happen, and sales driven organizations, you might often hear things like we need this to close this account. But it’s the job of the product team, writ large product managment/engineering to think about how are we going to draw the company out? How are we going to make it bigger? And by thinking about the customer in the true sense, you get a lot of positive effects.

Now thinking about the customer, the true sense is really like, how do I create, how do we create customer value? Now, people talk about this all the time, but they often don’t appreciate the value of this because the value of this is not just about the customer, but it’s about the company you work for and getting rid of that second culture clash, that culture clash around the product team, between other people in the company. The fundamental person you want to get alignment is with the CEO.

And the CEO’s job is to create a company with increasing value in a sustainable way, and a sustainable company. You want your next round. If you’re a private company would be larger than your last, if you’re a public company, you need to show growth. The reason this works is, it’s in the line with your users.

Your users only buy from companies that are going to deliver value to them. So if you’re focused on customer value, you will tend to get more customers. More customers means more revenue. If you’re doing it with unit margin, if it’s profitable on a unit basis, you’ll grow a profit for the company.

The value of the company is the sum of all future cash flows. That’s what your CEO wants. And that creates alignment that breaks down that second culture clash. If you can talk to the CEO about, if we do this, we’re creating more customer value—and the side effect of the customer value, not the primary goal, but the side effect of the customer value is we’ll get more revenue and more profit and you can talk in that way.

Then the conversation with the person in sales, who might be responsible for closing just this one account or marketing or someone else becomes the noise. Now I’m not saying you will never hear that. There may be some account that’s big enough that, of course, you’ve got to shift some something on the roadmap for, but the primary thing you’re doing by creating customer value will be engaging in a conversation with the CEO about how you solve the CEO’s problem about growing.

How do you know if you’re delivering customer value, look at your roadmap. If the majority of your activities don’t direct change for your user, you’re not creating customer value. I’m gonna talk about how to do that in a moment. You should measure the value your team has delivered and have that conversation with your team all the time.

And every member of your team, engineering and product members, both, should know why they’re doing it. What value they’re delivering? Who do you serve? Why or why is what you’re doing for them important? How does it change their lives? And they should be able to argue one story over the other and how that does that.

And this is not just product managers, arguing the stories. The engineers should argue for them. And by the way, the product managers should you with the engineering about architecture. Help me understand this, help me how this gets there, but that only happens in context of people understanding customer value.

That’s the first thing. Alignment, between product and the engine engineering about thinking about we build a product and alignment of who we serve alignment with the CEO. But how do you know if what you’re doing is serving? What is the mechanism you use?

Now? People often talk about metrics and you’ll often hear engineering talk about velocity and cycle time and PR response time, and frequently they talk to the CEO about these things. And that creates a problem. And product management has similar kind of things. They often talk to CEO just about roadmaps or user stories.

But that creates a problem because both of those metrics are internal metrics. These are efficiency metrics that talk about how we’re doing inside, but these are value metrics about what we’re doing for the people we serve. Once again, the people we serve are outside, our customers.

So what I recommend to you is thinking about the roadmap as a series of bets. You don’t actually know before you start something exactly what your customers want. Your customers don’t know, you can ask them, but they won’t know how to tell you. And so the things in the roadmap are a series of bets that hopefully are directionally correct, but not specifically correct.

The job of a product manager is impossible. If it’s measured by, I know exactly what people want. I tell CEOs all the time there’s, a class of CEOs who think they’re Steve jobs. And I have this conversation. I have it in a slightly more polite version than this, but it goes, I know how many Steve jobs currently exist in the universe.

There used to be one. Now there’s not, we need to have a series of bets on a roadmap by which we discover what people want. And the bets look like this, these epic statements, everything on the roadmap gets an epic statement. We believe by doing this feature for these users, they will get this outcome.

They will get this outcome. And we’ll know it when we see this metric move. But everything on the roadmap that you’re doing for an external user should have a thesis like this. You don’t have to use this exact format. There’s other formats you can use, but I strongly recommend a well-known format that you make these bets with and you’ll see why in a moment.

One reason is not just that, you know what you’re doing, but there’s a secondary benefit, which is internal alignment. Think of everybody in the company as a vector. Now how many of you took linear algebra in high school or college, but vectors have two attributes. There’s a magnitude and a heading of direction.

Magnitude is how big it is. The heading is where it’s going. If people don’t know the why, it’s like a tug of war every day, product managers are making decisions. Engineers are making decisions and there’s three or four ways you can code anything. And many, more ways that you can decide what user stories you’re going to do, UX people with what UX is going to look like, and they need to make these decisions every day in real time. Without knowing the context, they’re not likely to consistently make the right decision. Epic statements state the context. You can then ask if I do it this way, does this help get us closer or further away creating user value?

If my teams know the context in general, their vectors are going to be pointing in generally the right direction, as opposed to a tug of war where one set of people are pulling one way and other people are pulling another and you have some random Brownian movement in the middle and you might go one way or you might go another or worse, multiple ropes pulling.

You find that people align. And the vectors alignand you get pulls all in the same direction. And so having the epic statement allows people to make decisions and allows the squad to have conversations among themselves about Hey, why are you doing that architecture?

How does it help us get to the goal or engineer talking to product manager? I understand what you want. I understand why you want it. If we do it, it’s going to take a long time.On the other hand, I could do it like this and get 80% of it done at 20% of the time and have these other features. It engages a conversation between the engineers and the product managers.

It breaks down that first culture clash, because we’re not two teams. We’re one on the same goal.

[00:18:34] Janna Bastow: David, do you have time for a question? How do you accommodate for diversity in this model?

[00:18:42] David Subar: So diversity among thoughts or diversity among general diversity hiring diverse?

[00:18:50] Janna Bastow: Diversity of opinion.

[00:18:51] David Subar: I love that question. You want diversity of opinion, right? I’ll talk about it a little bit later about how do you empower teams? How do you empower teams to operate on their own? And there’s a whole other presentation I’ve done, which I’ll reference later about commander’s intent and how you have empowered teams that are aligned the same way.

But I want my product managers, my engineers to disagree, and I want them to disagree with me. Because different people have different points of view because some are closer to the data, some are broader, but diversity of opinions starts with defining that epic statement.

Why is this important for the customer? At the end of the day, the product manager gets to make the product decision. The engineering leader gets to make the engineering decision, but I want the people to care and argue academically, about given this why, here’s the best way to accomplish it.

And when I sit in meetings, I will look for the people that aren’t talking. And I will ask them, what do you think. It’s important to draw them. Out also, by the way, if you are the most senior in the room, you need to talk last, your voice is loudest, louder than anyone else in the room.

Even if you’re quiet. If you want diversity of opinion, and by the way, you should, you need to bring that. There’s other techniques. There’s Fist to Five, which I won’t go over now, but if someone wants, I can explain or I can direct people to it, which is how do you get simultaneous opinions without the loudest person in the room talking.

But there’s different techniques to pull opinions out from people. And then you do also need a resolution and the way to empower the person who gets to make the final decision. I had a CEO who did this. I thought it was brilliant. We’d be debating something, and the debate would go on for some period of time, the CEO would look at us and say, whose decision is this? Now, all decisions could have been the CEO’s decision, because he was CEO and ,someone would say it’s Karen’s decision. And so he would turn to Karen and say, okay, Karen, you’ve heard the different opinions.

What’s your call? So it’s about seeking diversity of opinion, getting to solution and empowering the people to make the solution.

[00:21:37] Janna Bastow: And to echo that Alex in the chat just said having a difference of opinion is really important. The key, he said, is to ensure that teams are empowered to work through opinions and arrive at a decision. Otherwise it turns into unresolved tension.

[00:21:52] David Subar: That’s right. And Alex’s point about teams being able to work through it is also critical.

The CEO, as I said before, can make every decision in the organization. The problem with that is no person scales more than 24/7. And by the way, if the CEO makes every decision, people will tend to find new jobs where they’re more respected.

[00:22:15] Janna Bastow: One of the things that I always say is one of the most dangerous things for a business is a product manager who thinks they have all the right answers.

Your job as a product person is not to have all the answers. It’s to ask the best questions and to surround yourself with the people who have those insights and to make the space for those insights to come together, to create something more out of it than just your own take on the product.

Otherwise, what you’ll end up with is the singular product manager’s idea of what the product should be. And almost certainly, it’s never going to be as powerful as what the team together could come up with.

[00:22:49] David Subar: That’s right. And that’s why it’s a product team, with product managers and product owners and engineers and QA and UX whoever’s on it.

That’s why it’s a team doing it. And that’s why it’s a conversation outside of the team about who do we serve, because it’s not only the opinion within the team is clearly the most important, but also there’s colleagues you have in sales and marketing, who actually do know some stuff that are important and not just sales and marketing.

And so aligning to the same vision creates alignment within the people that you’re working with. We talked about alignment. We talked about measurement. Now I talk about review because it’s not enough to say we’re all serving the same goal and we all have a statement of how we’re going to serve them.

But you got to ask how you did. From what I was saying before that it’s being the product managers in a possible job. Because you can’t know exactly what the user wants. You’re making a series of bets. Some of those bets are going to be wrong. Some of the bets are gonna be wrong. By the way you want some of the bets be wrong.

I could make every bet a right bet by making no bets. You want some of the bets to be wrong. But given that some of the bets are going to be wrong, you want to learn from them and people know how to retro sprints. Hey, we just did a two week sprint one week sprint, whatever your sprint cycle is, there’s similar things in Kanban and other agile methodologies.

What did we do well that we want to keep doing? What do we want to do differently? How? What people don’t do frequently is retro what their bets were on the roadmap. What went well? How did we serve our users better? How did we miss? We did a lot of effort. We didn’t serve them better. We’d serve them worse.

And what do we learn from that? You’ve got to retro your releases, but you can’t retro them the day that they end, like a sprint. You’ve got to wait until some users have some time to do it. And maybe you even need to retro it more than once, but two weeks or three weeks out after delivery, or if you’re a big B2B environment, maybe it’s longer, you’ve got to retro them.

So you’ve learned what you’ve done. And so you could think about how do I make these bets better? This is critical.

But it’s not enough just to retro them. You’ve got to be transparent too, not just within the product manager and engineering team that you’re working with, not just within your squad, but with the rest of your teammates. You got to report to the other departments, other executives, how you did on your best.

Now, this is a really scary thing. It’s scary to go to the CEO and say, we made these bets. Maybe we made five bets and two of them did really well, hit it out of the park. One of them did okay. And two of them just didn’t do well. Didn’t do well. It’s a scary conversation to have, but to get alignment with the CEO, you need to be transparent to the CEO. The CEO is going to figure it out sooner or later, anyway, because by the thesis of we create customer value. And as a side effect of customer value, we create revenue and profit, and that creates company value for us. The CEO is going to figure out whether you did it anyway.

So you might as well be upfront with the CEO, upfront with your partners and talk about it. But the key is, not just to say, here’s the things we did well, and here’s the things we did differently on. It’s the value of the retro. Here’s what we learned. And more importantly, here’s how we’re changing the roadmap next.

Here’s how we’re continuing to improve customer value and therefore revenue and profitability and cashflow and the value of our business. You’ve got to have a full cycle of, we know who we serve, we make bets in this format, we release product, we measure it, we update the roadmap based on it. Wash, rinse, repeat, do it again.

And again, and that is the cycle that gets you through the culture clashes gets you to alignment between product managers and engineering people in the squads, and those squads with the rest of the company. That’s the cycle. That’s important. Now I want to, now that is not enough.

We talked about the five things to overcome the culture clash, but there’s other things to know to create an effective culture.

There’s four other additional things to create an effective culture

Organizational models. I met Kevin Goldsmith, who was one of the executives at Spotify. Brilliant guy. If you ever get a chance to know Kevin, you should get to know him.

And I recommend listening to the interview that I did with him, because he says a lot of brilliant nuggets of things, but I’ll tell you a few of them here. There’s a worship of the Spotify model. Hey, we’re going to have a squad. And we’re going to have guilds and we have tribes and this is the way they work and we’re going to do that because it was so successful at Spotify.

And there’s a counter worship where people say it failed at Spotify. They’re not doing it so we know it failed. And so you shouldn’t use the Spotify model. And Kevin says something that’s interesting. That’s neither of those. Kevin said, we define an organizational model for the business problem we have, and it was successful until it wasn’t.

Our business problem was, we were doing music streaming and we knew there were going to be large companies coming into our space that had a lot more capital than us, a lot more revenue, better brand. And if we’re going to try to just outspend them, it would never work, but we could do something that they couldn’t do.

We could innovate really quick. And so we created an organizational model. We had a bunch of independent squads that worked on stuff cause they knew who the customer was and they were focused on the customer and they would work on things independent of each other. And so I said to Kevin, wait, hold on.

That means two groups were doing the same kind of code to do the same kind of stuff you said. Yup. That’s, inefficient, he goes, yup. We don’t care. We didn’t care because our goal was not code efficiency. Our goal was innovation. We created these independent squads to be innovative. And I said to him, didn’t that cause problems? He said, yup. You said our interfaces for two different parts of the Spotify app looked different for the same kinds of buttons. We made an organizational model trade-off to solve the business mission that we had. Out innovate who our competitors would be, who we didn’t know at that point, but maybe Microsoft or Apple or Amazon, we didn’t know who was going to be, but we needed to innovate.

And we created an organization, the model to do it. And he said, and then we won. And so Spotify doesn’t do Spotify. Doesn’t do that organizational model anymore because we no longer needed to out innovate. And so the memes about Spotify is great. We should do exactly what they do did. And the memes about Spotify model is stupid. They don’t do it so clearly it failed. Both are wrong. We created an organizational model that worked for us at the time. And then that organizational model changed when our needs changed. Kevin strongly stated, you need to understand, you need to create an organizational model that supports what your business goals are.

Now notice he didn’t say to create engineering efficiency or product management efficiency. It’s what the business goals are. So once again, this is about alignment to where you’re joining the company and what you need in alignment with the CEO. This is completely consistent with this. Anyway, I recommend you listen to the interview with Kevin or any other place Kevin’s spoken. He’s very forward about this concept and a brilliant guy.

So organizational models, that’s one thing. Personnel, none of this works if you don’t have great personnel.

And there’s three things you need to do to have great personnel. You need to recruit. You need to retain well and you need to fire well. The third of those is the hardest, but the good news is, if you have alignment to a customer, all of these become easier.

Engineers and product managers have choices of jobs. I’ve told CEO’s that everyone in the engineering and product management staff can walk out of the office today and get a new job in three days. And if they can’t, I don’t want them here either. So you have to assume that everybody on the staff has plenty of options.

They don’t have to be here and we don’t have enough money to pay people enough to essentially buy them. Google’s got more money than we have, whoever you are, or Facebook or pick your company. And interesting projects, turns out there’s a lot. What we have as a differentiator, is who we serve. So I had this job offer at a fantasy sports company and the CEO was great.

And back when people went to offices they had beautiful offices and they had a hundred million dollars in investment and it looked like a great opportunity and I really want to work for the CEO and they made me an offer and I thought about it and I thought about, and I thought about it and I didn’t take the job.

The CEO, his name, Richard, I didn’t take the job. I called Richard up. And I said, thank you for your offer. And I really want to work for you, but I unfortunately can’t take your job because you know what? I don’t care about sports. I can never be great at this job. I can only be very good. And by knowing who you serve, that’s a differentiator, here’s the impact we make at this company. And if this is something that you’re interested in, that’s our differentiator.

You should come work here.

You need a great team. And having that solves both the recruitment problem and at least part of the retention problem.

We talked about organizational model, personnel, and now it’s about empowerment. It’s important to not tell people what to do. What’s important to do is set the goal set for people. Hey team, our goal is to do X.

Please argue with me, ask me hard questions about why we need to do X and they, you should encourage them to ask you hard questions, and then you should have the conversation with them. The argument with them, debate with them about why they’re going to know some stuff you don’t know as a leader. And you’re going to know some stuff they don’t know because you have breath after you decide on the, what don’t tell them that.

Go to the team and say, your job is to come back and tell me how you’re going to get us to this goal. I trust you. And when they come back and tell you, your job is to ask them hard questions, do not tell them if you tell them things, they will tend to do what you say. That’s not what you want. You want to hear their opinions and you want to ask them hard questions.

And the hard questions you may understand that they didn’t understand something or you may come to understand that they have some data you don’t have. Now you’ve agreed on goal and implementation your job now is to let them run. You have to let them run. You have to get impediments out of their way.

And you check in with them on status to make sure they’re getting aligned. That’s the commander’s intent. That’s the empowerment model in a nutshell.

And finally, the environment. All of this only works, if you have a company that can grow or is growing, you have the ability to lead the team, you are empowered the same way I suggested empowering the team to lead the team, you can give them what they need to do their job, you can create that environment, and you have a seat at the table. That’s the environment that you need to exist in. That’s the environment you need to set up for your team.

And if that’s not true, you need to make it true, we need to find a place that is true.

So I’ll leave you with one last thought. The author of The Little Prince wrote other material, a book called the Airman’s Odyssey. And he said, love it does, it is not about looking into gazing at each other, but looking outward together in the same direction. I argue, this is exactly right, but it’s not just right about being in love with someone, it’s right about collaboration and creating a culture of service, of creating a culture for product managers and engineering.

It’s not about just how do we make our jobs better, but how do we, who do we serve? How do we focus on them? And, how do we make their lives better gazing the same direction for a same mission. So if anybody has any questions, anybody wants to talk more about industry. There’s a variety of ways to get ahold of me.

I’m glad to just chat with people. Anyone want to chat, feel free to reach out. So that’s what I got.

[00:38:07] Janna Bastow: Wonderful. Excellent. Thank you so much. And there’s actually a great question that somebody wanted to clarify.

One of the other points that you put up there towards the last slide, I think there were some criteria in there going, you’ve got to have the empowerment, you’ve got to have a seat at the table. And somebody asked, was that a message for CTOs and CPOs?

[00:38:29] David Subar: I think it’s a message for everybody. I think it’s a message for everybody. I want to work with empowered teams.

I think that companies can only scale it up there have empowered teams. Is it more important for CTOs or chief product officers? No, it’s not. If you’re CTO and chief product officer, if you want to be successful, it means you want your teams to be successful and they have to be empowered.

What to do if you’re in a company that’s not empowering you?

I read this great article by how do you deal with managers that micromanage? And the answer was, I don’t want you to know that this works in all cases, but I thought the answer was really interesting is do everything they ask plus a little bit, empower yourself to do a little more, and demonstrate to your manager, you asked for A, B and C and I did that and gosh, we’re successful on that.

And by the way, while I was there, I did D and I think this creates value here. Take a little bit of expansion. Now that starts engaging the conversation, right? If your balloon is this big, you can’t expand it to that. You can only go from this to that. So it might take time, but it might engage in a conversation, but you might not be empowered because the person you work for is scared.

The other thing is breaking bread with someone is a very powerful thing. Sitting down and having a meal with someone where you learn about oh, you have a significant other, who’s that significant other, or you have kids, you don’t have kids, you have a dog or a cat.

And when people get to know each other, they start to be someone you can trust. And so that also expands. So neither of those might work, you might have to get another job, but you don’t necessarily have to get another job.

[00:40:16] Janna Bastow: I remember an early boss in my career really opened my eyes when they reminded me that it’s easier to ask for forgiveness than permission. And they basically gave me implied permission to go do some things take some resources, take some, effort and do some things that were not necessarily by the book, but allowed us to get some things done.

A really clear difference that I want to point out to anybody though. Don’t put up with a toxic environment. There’s a difference between not being empowered and not being able to do parts of your job, which is not fun. It’s sucks.

But don’t put up with a toxic environment if you’re in that and it doesn’t feel right. Get out, there are plenty of people hiring.

[00:40:59] David Subar: By the way, I had the opportunity to meet Grace Hopper, the woman who originally said, it’s easier to ask for forgiveness and permission many years ago, I don’t know how old she was, but I think she was ancient at that point.

She was amazing. She was a fireball, even I’m guessing she was in her eighties and she was giving a presentation, a company I was working for. And I got to spend a little time with her. And in her, even in her eighties, she was empowered. Like she was frail. She was walking with a cane. She was bent over and the most powerful person in the room, by far.

[00:41:36] Janna Bastow: I love that. All right. Let’s try to do some quick fire questions here. How do you engage a CTO that does not prioritize to measure what was released? Any tips on that?

[00:41:48] David Subar: Clearly that CTO knows if the servers go down and when the servers go down, clearly the CTO is very attuned to getting them fixed because sooner or later the CEO will figure it out. And that won’t be a pleasant day. So there’s some type of retro the CTO does, even if they don’t think about it that way.

I think the conversation goes with Hey, my job is to try to create a product that people like I’m going to be wrong. I would like to know where I’m wrong. Cause I want to do my job better. And I would like to be your partner in this.

Now they might just go say pound sand or something, not so nice. But then you, then, if you’re not the chief product officer, you might need to engage the chief product officer to engage in the conversation with the CEO. Or if you are the chief product officer, you might need to engage a conversation with the CEO to say, Hey, here’s what I’m trying to do.

Here’s why I’m trying to do it. Here’s why I need a partner and I don’t have one today. Can you help me create this person into a partner? But this goes back to if you’re aligned with the CEO and your environment, other people generally will have to fall in mind or find another job

[00:43:13] Janna Bastow: Excellent. Next question. If you can’t come up with any kind of success measure for epic statements, should you not do that yet?

[00:43:21] David Subar: I would question why you’re doing it. If you don’t know the value you’re trying to create, I would ask him like, why are you doing this?

[00:43:29] Janna Bastow: Yeah, absolutely. I agree with that.

Everything should be able to be justified by your north star metric. And it doesn’t necessarily mean that everything has to get us revenue, but you should be able to understand what impact it’s going to have for the business. Ask those five whys and dig down as to what it’s actually doing there.

And if you can’t answer that, if it has no point place in the backlog

[00:43:53] David Subar: And there’ll be some things in the roadmap that don’t serve because for not everything will serve the customers. Some like we’ve got to refactor this bit because it’s going to get us, it’s going to get us out of tech debt.

That’s as long as those are okay, too, but you better have a why.

[00:44:07] Janna Bastow: Actually. This is something I was going to mention. Cause you said something about showing value on your roadmap and it’s important not to misjudge value as creating new things for the customers to play with. That doesn’t mean new features, sometimes value to customers means helping them realize the value that you’ve already created in your product.

Helping them see how to use or changing how you price or package things. There’s lots of ways to create value for your customers. That doesn’t mean creating new code or creating new features for them.

[00:44:42] David Subar: Yep, exactly. Exactly.

[00:44:45] Janna Bastow: As a product manager, how do you get your team to be comfortable with ambiguity?

[00:44:56] David Subar: I think the answer is, the MVP model. We don’t know we’re going to build small and we’re going to explore the space and iterate through it. This is classic agile, right? What’s the smallest possible thing that we can build that still has value.

There’s a counter question is someone asked me the other day, is what do you do when you have engineers working on something, and it turns out it didn’t add value. Don’t they feel bad about it? And the answer is, yeah, probably if they look at the mission and the small, but if you look at the mission to large and we’re going to try a bunch of stuff, some are going to work in some aren’t then what did we learn is the value is the thing you really created.

Yeah. And so what is the minimum we can invest to learn the next thing. And here’s another way to look at it is if I’m going to start up and let’s say we have 18 months run rate. So with 18 months before we have to have our next round, we better start looking for our next round in six months before we run out, because we’ll lose all leverage.

So we don’t really have 12 months and we need to show business progress in that 12 months. And if I do a release every week, I have 48 times to try to get this business forward, I’m just making easy math. And so how do I use those 48 bets? You actually have a lot more than 48, but how do I use it?

[00:46:20] Janna Bastow: That makes a lot of sense.

[00:46:21] David Subar: I love how you’ve I take that to you think about it from both sides. And I think that makes a lot of sense. All right. On that note I think we’re out of time for questions. Thank you so much for everyone, for sending through your questions and getting involved in the chats and a huge thank you to David.

[00:46:38] Janna Bastow: Thank you so much for getting involved in sharing, somebody called them knowledge bombs earlier. Keep an eye out for the next webinars that we’ve got coming up.

Bye-bye everybody.

Watch more of our Product Expert webinars

How to ‘Do’ Growth Product Management

Learn practical ways to build and execute a product-led growth strategy and demonstrate the outcomes you’re delivering and the needles you’re moving.

How to Set Product OKRs (The Most Effective Way) for 2025 with Ben Lamorte

Learn the best way to set and use your Product OKRs from Ben Lamorte, OKR expert and author of Objectives and Key Results: Driving Focus, Alignment, and Engagement with OKRs.

Why, How, and When to Kill a Product or Feature with Stephanie Musat

Watch as we share everything you need to know about why, how, and when to kill your product or feature without ruffling any feathers in the process.

You’ll also enjoy reading these articles