[On Demand] Product Management Webinar

OKRs vs. Roadmaps Deathmatch with Bruce McCarthy

We kicked off the year with the deathmatch you’ve all been waiting for OKRs Vs Roadmaps – Who will win? Can they work together? Did John Doerr get OKRs wrong?

Watch the battle of the year and explore the topic with special guest, Bruce McCarthy, Founder of Product Culture, and host Janna Bastow, CEO of ProdPad and inventor of the Now/Next/Later roadmap. They’ll be sharing their expert knowledge, real-world examples and exploring core theories and best practices.

About Bruce McCarthy

Bruce McCarthy, Founder of Product Culture, helps companies like EGYM, Vistaprint, Localytics, Huawei, and Kaleyra achieve their product visions through forums, workshops, advising, and private coaching. He is President Emeritus of the Boston Product Management Association and a head judge at the annual Harvard Business School New Venture Competition. Bruce co-wrote Product Roadmapping Relaunched: How to Set Direction While Embracing Uncertainty.

Key Takeaways

- How can OKRs drive your Roadmap

- What did John Doerr get wrong about OKRs?

- How to use OKRs and Outcome-based Roadmaps to Measure Success

- How OKRs can be used to empower your Product Teams

- What is more important your OKRs or Roadmap?

[00:00:00] Janna Bastow: Welcome to the ProdPad product expert fireside series of webinars. It’s a series of webinars that we run here. And every time we run it, we bring in a different product expert, as you might imagine. And all of the webinars that we run here are recorded. They are a mix of presentations and firesides. And today’s going to be a fireside between myself and Bruce. We always bring in experts. And it’s always with this focus on insights, the focus on the content and the learning and the sharing, and these experts bringing in their experiences that they’ve gained over the years.

So today is going to be recorded, and it’s going to be shared with you. So you’re gonna see a version of this out on our YouTube channel. So subscribe there, if you want to get the first eye on it it’ll be up on our website. And because you’ve registered here today, you will get a copy of this sent to you soon. And you all gonna have a chance to ask questions here today. So drop them into the Q&A as soon as you have a question. I’ll try to get to it as soon as I see it or at the end as we go.

Before we kick off into the intros to Bruce and the topic of the day, I wanna tell you a little bit about ProdPad before we get started. So this is originally a tool built by myself and my co-founder Simon because we were both product managers ourselves. And we just needed tools to do our own jobs. We needed something to keep track of the experiments we were running to try to hit the business objectives that we had to solve the customer problems that were in front of us, and to keep tabs on all the ideas and the feedback that made up our backlog.

And so building ProdPad gave us control and organization and transparency. And it wasn’t long before we started sharing it with product people that were around us. And today it’s used by thousands of teams around the world. So it’s free to try, you can jump in and start a trial today. And we even have what we call a Sandbox mode, where you have examples of product management data. So you can see how things like lean roadmaps, OKRs, experiments, and everything else fits together in a product management space. And our team is made up of product people. It was founded by product people, we’ve got lots of product people amongst our team. Start a trial and then get in touch and let us know how you like it. We’d love to hear from you.

And on that note, let’s introduce you to Bruce. Everybody, this is Bruce McCarthy. Say hi to Bruce.

[00:02:25] Bruce McCarthy: Hi, everybody.

[00:02:26] Janna Bastow: And Bruce, say hi to everybody. So Bruce and I first crossed paths in we were talking about this the other day, it was 2013. So this is way back when ProdPad was brand new. And Bruce was actually working on a product concept in a similar space. And it’s called Reqqs, like for product requirements. And we were putting this together. I reached out to him because he published some research on the product tool space. And I wanted to thank him for his work in it and set up a Skype chat to talk through what we were learning in this sort of nascent new space.

We ended up having a great chat and we kept in touch. Since that time, Bruce, shifted focus to work directly with teams as a consultant and later as a renowned speaker and author of the Product Roadmaps Relaunched book where, there it is, where I had the opportunity to work with him and his co-authors by contributing the foreword.

[00:03:26] Bruce McCarthy: Thank you very much.

[00:03:28] Janna Bastow: Of course thank you. So Bruce is the founder of Product Culture he helps companies like, EGYM, VistaPrint, Localytics, NewStore, and others achieve their product visions through a combination of hands-on learning, advising, and coaching. He is president of the Boston Product Management Association and head judge at the annual Harvard Business School New Venture Competition. And as I said, he co-wrote the Product Roadmap Relaunched book. So, a huge name in the product roadmapping space. So hugely honored to have him joining us here today. And thank you so much for joining us here today, Bruce, great to have you.

[00:04:15] Bruce McCarthy: My pleasure. Thanks for calling me up.

[00:04:18] Janna Bastow: Of course. So Bruce we’d love to have you tell us a little bit about how you got into the product space and what sort of inspired you to move into this path?

[00:04:34] Bruce McCarthy: I was a product manager like you are, many people on the call probably are for many years and I worked my way up through the ranks in different companies, different sizes, startups, as well as huge companies like Oracle to being head of product. And along the way, I ended up officially or unofficially in charge of lots of related things like engineering or agile or design or partnerships, you name it. And for me, the interesting part, the fascinating part of product has always been the connections between all of those different functions.

The puzzle that you can put together with all of those pieces, and make something fantastic or something that people want to actually have and use and look at. And it’s, to me, the roadmap, in particular, was always the place where that all comes together, where the picture becomes clear from assembling all of those pieces. So it made sense as a place for me as a practitioner to focus my efforts, and I began to speak at ProductCamps and conferences and so on about how to do it in a compelling way, especially after lots of failed attempts at doing it the wrong way on my own part so I was sharing what I was learning.

And really really found the reason I ended up writing the book, the reason I ended up becoming an advisor and a consultant is that it’s hard to do it well, just like most of the product is hard to do well and a lot of people don’t need to go through that trial and error phase that I went through if they can have kind of a map of how to do it right. So that was where the book came from, that’s where my practice comes from.

You won’t be surprised to learn that because I think roadmaps are where it all comes together, when working with companies on roadmapping, I end up working with them on OKRs as well. I end up working with them on team organization, dependency mapping, culture aspects, decision making, on just about everything because it’s that holistic phenomenon that product is that really matters. And roadmapping is just writing down the result of that process.

[00:07:16] Janna Bastow: Yeah. That’s actually a really good point. That’s something that I see here at ProdPad, as well. So many people come in because they want to solve that roadmapping problem because that’s the piece that bubbles up in this frustration at the end of the month.

[00:07:28] Bruce McCarthy: Yes.

[00:07:29] Janna Bastow: They go, “Oh, I need the roadmap done by Tuesday because someone’s going to get upset if it’s not part of the board pack.” But really, roadmapping is this process, and it involves you need to have a whole lot of thinking behind it that isn’t just creating a roadmap, right? Creating the roadmap is actually the easy part if you’re just thinking about putting the things in the places, but the roadmapping process is so much more.

[00:07:56] Bruce McCarthy: That’s right.

[00:07:56] Janna Bastow: And this-

[00:07:57] Bruce McCarthy: Or fool themselves into thinking that doing a roadmap it means creating a document?

[00:08:02] Janna Bastow: Yes.

[00:08:04] Bruce McCarthy: Yes, that is the end, the output at the end. But that’s really just, writing down the result of quite a lot of, quite a lot of work and process and input.

[00:08:15] Janna Bastow: Roadmap, not just a pretty picture, right?

Yeah, exactly. And this is where you start getting these fights between OKRs and roadmaps, right?

[00:08:26] Bruce McCarthy: I think so. The way I think about it is that people sometimes they have a little bit of religion about whether they should be doing a roadmap or they should be doing OKRs and that the two are just different and orthogonal to each other and, or even their different philosophies about what what what how you run your team. And I think honestly, that’s a mistake. I think if you’re thinking about roadmaps in kind of the traditional way as a list of features and dates, without a lot of context, then you gradually begin to ask yourself “Why are we doing these things? What is the point? What is the end goal of working on all the things that we’ve written down on our roadmap that we’re supposed to be working on or that we’re supposed to be delivering?”

And if you take it from the other direction, if you take it from your OKRs team, and it’s all about outcome, outcomes, right? That does cover the why hopefully. You’re trying to grow revenue, increase the number of customers and improve results for those customers if you’re focused on them, but then the next question after people absorb your, “We’re gonna move this number from here to here” is, “Okay, how? What problems do you need to solve in order to make that happen?” So I think one cannot properly tell the whole picture without the other.

[00:10:03] Janna Bastow: Yeah, I get that. And you know what, it was quite funny because when we first started putting the word out about this webinar, somebody called us out and said our title was bait. And I guess they saw through that OKRs and roadmaps are really in a death match, right? We’re not gonna kill one off today and be done with it. “There’s your answer. OKRs lose, Long live the roadmap” But we were talking about this just last week, like where the contention between roadmaps and OKRs come from. We’ve seen the likes of Marty Cagan saying things like, “Don’t do roadmaps, the answer is OKRs.”

We’ve seen people on one side or the other and many others, like taking one side or the other. One team’s-

[00:10:48] Bruce McCarthy: And I know why people say that. And I know why Marty said that.

[00:10:52] Janna Bastow: Yeah.

[00:10:52] Bruce McCarthy: That is because creating, putting down a roadmap, at least in the traditional way people do it, feels like a kind of a no-win scenario. You’re trying to predict the future about what features you’re gonna ship on what dates out like 12 months or three years even.

[00:11:11] Janna Bastow: Yeah.

[00:11:11] Bruce McCarthy: And that’s just an illusion, we don’t have that kind of crystal ball about how long things are really gonna take, or whether priorities will change, or whether we’ll learn something, hopefully, from shipping feature A before we even begin on feature B. All of those things are variables that are just going to change and that we have incomplete information about. And so if you think of a roadmap as a list of features and dates over the course of a long time then I understand why people would say, “Look, don’t do that. Let’s talk about outcomes. Let’s talk about the results we wanna get. And let’s remain flexible on precisely what features we ship.”

I would say, “Let’s take that approach with the roadmap rather than let’s throw out the roadmap.” I would say, let’s, in, in this book that you mentioned that I co-wrote with see C. Todd and Evan and Michael we talk about there being a few key components to a roadmap that I think are missing from a lot of traditional roadmaps.

The first is, what is the product vision? And the product vision is a future world where a customer is gaining a benefit. And they’ve chosen your product because it does it, helps them achieve that benefit better than any other. So that’s not a list of features. That’s a destination. That’s a pretty picture to go back to that puzzle picture analogy of the future. And then what problems do we need to solve for the customer to make sure that we can deliver that benefit? I call those themes but they’re basically the problem statements or jobs to be done for the customers, right?

And then the third of the major component is actually the business objectives. How are you going to do this in a commercially viable way that allows you to make money and grow as an organization so you can keep on serving the customer? And the most popular way today of describing business objectives is, of course, OKRs. I think they have to be part of your roadmap. I think they are they are half of the story of why. If the vision of the customer being successful and happy and feeling empowered is, half the business the, moving the business forward is the other half of the why.

[00:14:01] Janna Bastow: Yeah, exactly. And that’s actually a really key point is when we talk about what a roadmap is, you get completely different takes and completely different mindsets around it. When you say roadmap to some teams, they automatically jump to colorful Gantt chart, a list of features and deadlines for better or worse, right? That’s what’s in their head and that’s what we’re up against.

And other people they go, “No, that’s not what a roadmap is, we’ve moved away from that.” And of course, we’re talking about something more lean, right? And so why are we vilifying the roadmap? And I think this is where the confusion around whether roadmaps and OKRs can work together is, because, of course, a list of dates and features is not going to just work automatically with an outcome objective focused framework, like OKRs.

They’re just going to hopefully, OKRS will win that fight. But-

[00:14:58] Bruce McCarthy: Yeah, hopefully. If that’s what OKRs are fighting against, they should win.

[00:15:02] Janna Bastow: Yeah, exactly. Exactly that. But I think, OKRs actually need the roadmap to provide that sense of progression, to provide that sense of, what do we actually do? Because OKRs aren’t the full picture. OKRs are simply objectives and key results at the end of the day.

[00:15:19] Bruce McCarthy: Well, that’s right. So let’s, talk about definitions a little bit. I actually in my pantheon my, components of OKRs, I actually incorporate four different concepts. So you mentioned two, objectives the fuzzy aspirational thing, inspirational thing we are trying to achieve, like getting some real traction for our newly launched app.

[00:15:43] Janna Bastow: Yeah.

[00:15:44] Bruce McCarthy: And then there’s the OKRs, which are the measurements of progress. Okay, if it’s traction, then how many customers do we have? How many monthly active users do we have? How much money are we making those kinds of measures of traction, right? But there’s actually some other pieces that are complementary, that are immediately obvious that they’re missing when you start thinking about, “Okay, gang, what are we going to do now?” we probably need to do some research to figure out what’s working and what’s not working for those users, so we can get more of them.

If we want to move the needle to getting more traction, what do we need to do? There’s going to be some ideas, some initiatives, something that’s going to come out of that process, and we need somewhere to put them. So in addition to the objectives, the key results, I usually have a list of initiatives, at least that will be considered as possible things to move the needle.

And then I also usually have a fourth concept, which I call health metrics, or sometimes people call them KPIs. And they are things that you’re just always monitoring. Uptime. As long as it’s in the green zone, it doesn’t need to be an OKR. It’s just cluttering up your OKRs, as long as there’s nothing you need to do. But on the other hand, if it falls into the red, you wanna know right away and you need to take action. So I separate those out into their own bucket.

[00:17:20] Janna Bastow: So are these sort of like the Business As Usual sort of metrics?

[00:17:23] Bruce McCarthy: Exactly.

[00:17:24] Janna Bastow: Okay.

[00:17:24] Bruce McCarthy: Business As Usual is the way to think about it. And there’s kind of two subclasses in there. There’s the things that you always wanna just have in the green zone, like uptime, or say ticket response time to escalations from customers, things like that. And as long as they are green, then you don’t need to worry about them. If they turn red, you need to act and maybe put aside your OKRs until you fix it. If they’re chronically falling out of the green zone, maybe then you do temporarily need an OKR to somehow address that ongoing problem, fix the problem, and then retire it again as a health metric.

And then there’s also performance metrics. If you’re, say, an enterprise software company, you probably don’t want to make your sales goals into an OKR—that’s demotivating. And besides, the the product team can’t affect those things directly. But again, they’re a performance metric for the organization as a whole. And the management team is gonna be watching that number. So let’s acknowledge that and put them into this side bucket that, then again, doesn’t clutter up the OKRs.

[00:18:39] Janna Bastow: Oh, that’s really interesting. So I like the concept of those health metrics off to the side because it creates this baseline. It’s almost like saying, if the business is healthy, or if we’ve hit these like minimum things, if Business As Usual is happening as usual, then we can look at achieving our objectives, like putting the extra stuff into the objectives. But if something is on fire, if we’re not achieving our bare minimum, then we don’t put those resources into that. We need to go back and figure out why we don’t have uptime or why, you know, something’s on fire.

[00:19:13] Bruce McCarthy: Exactly. I’m seeing an interesting question in the chat. Where does product strategy fit into the hierarchy of vision roadmap, OKRs, initiatives? How does this differ other than being a higher level? I think that’s a really good question. To me if you have a vision of the destination you’re shooting for, and you have a set of business objectives that you can track, those OKRs that you can use to track your progress as an organization, and you also have a list of prioritized customer problems to solve that will help you move the needle on your OKRs and move stepwise to your vision, that is a statement of strategy.

You are saying, “This is our strategy for how we will achieve our vision and grow as a company. Because we believe solving these problems, making the customer successful makes us successful.” And to me that’s, a clear statement of strategy, it’s also the underlying philosophy of Product Culture is, we become successful by making the customer successful.

[00:20:24] Janna Bastow: That’s perfect. And Starr in the chat says, “Thank you for that.” That’s great. And I really like the concept of taking the OKRs and expanding them outwards, because you talked about having the initiatives and the additional health metrics. Is that similar? Because we were talking last week about the, themes and initiatives and the different terms. And you talked about the sandwich thing. Does that-

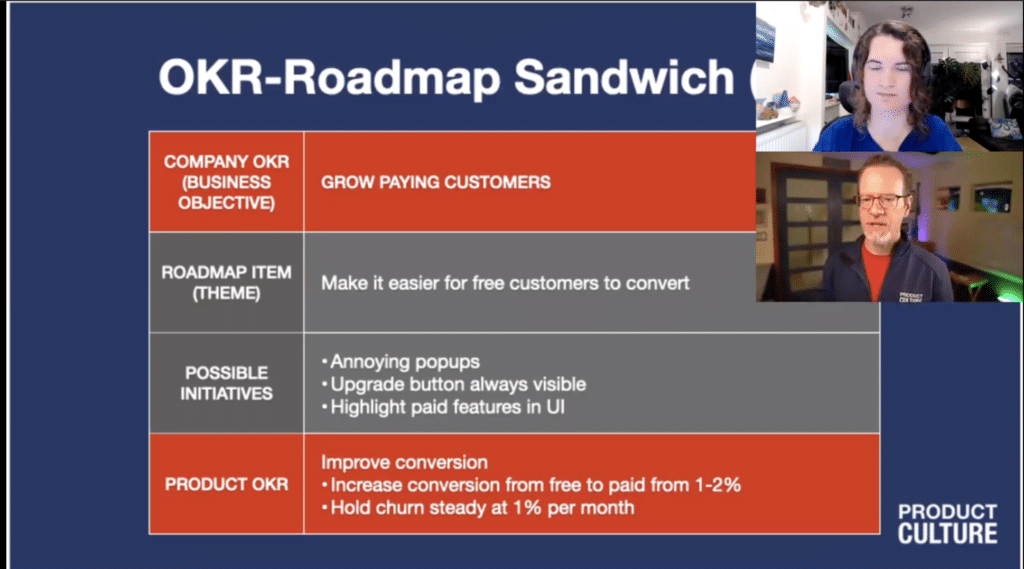

[00:20:48] Bruce McCarthy: Oh yeah, yeah. To me, the interaction between the roadmap and the and the OKRs is not just one to one, it’s it’s a little more complicated than that. And so I came up with this, the analogy of the sandwich. Because I think, at a high level, you wanna say these are the company business objectives, like revenue or customer acquisition, or margin or whatever it is.” And that drives us to think about some roadmap items that are customer problems to solve that we think will have that result. But then, how do we know whether anything that we put on the roadmap and we work on and we ship actually is working?

[00:21:36] Janna Bastow: Yeah.

[00:21:37] Bruce McCarthy: Usually there is some more tactical leading indicator that tells us that the feature we shipped or the problem we hope we solved for the customer, is actually making a meaningful difference that will have short term results that result in the long term company results that we’re looking for. So the sandwich is like, the OKRs are, company level and then there’s the roadmap in the middle in the gray here, and then there’s the OKRs, down at the product team level or the roadmap item level that says, “This is how we’re gonna measure whether or not this thing that we have proposed is performing.”

Now, you mentioned the word, when we were talking about this earlier, experiments, and I like that thought. But the way I think about it is, these experiments for me are inside of the roadmap theme. The roadmap theme is the problem to solve for the customer. I have a bunch of possible initiatives that might solve this problem, I hope, and I’m gonna prioritize them based on how likely it is that I think that they will solve the problem well and, compare that to the level of effort.

So I’m gonna try my best guess as to the best way to solve this problem. And the experiment is to see whether I’ve solved the problem. And then that, tells me that my OKR for that initiative is measuring the degree to which I’ve solved the problem.

[00:23:21] Janna Bastow: That’s cool.

[00:23:21] Bruce McCarthy: So a product team if they’re trying to grow the number of paying customers that’s going to take a while, but I can measure the change in a B2C environment with lots of volume. I can measure the change in conversion rates pretty quickly in a matter of days after I make a change to the UX or to the feature list or to something. And if it’s if I’ve moved from 1 to 2%, successful roadmap theme is retired, move on.

If, and this is critical, and the difference between a roadmap and like a project plan, if it doesn’t work, if this change that we made, has no meaningful impact on the conversion rate or it screws up the churn number then that experiment is a failure and the roadmap item is not solved. So we move on to initiative number two, our next best guess as to what will move the needle?

[00:24:29] Janna Bastow: Perfect. Okay, gotcha.

[00:24:30] Bruce McCarthy: Does that make sense?

[00:24:31] Janna Bastow: Yeah, I think so. I think so. And actually, Ryan in the chat has a question that it expands on that. He said, “If you’re understanding the sandwich analogy correctly, are you saying you have nested OKRs?”

[00:24:44] Bruce McCarthy: Yeah I am. I’m saying that there are company-level OKRs or product-wide OKRs, and then there are OKRs for a quarter for a given team. And that team might be in charge of an entire product, or just one piece of a product, let’s say, the onboarding process in, this example. People have a free version for a month, and then we wanna convert them to the paid version.

[00:25:13] Janna Bastow: Yeah.

[00:25:14] Bruce McCarthy: Maybe, a team owns just that part of the experience. And so there is a logical cascade of those OKRs. And this is at least one visualization of how they could interact with and inform the roadmap.

[00:25:30] Janna Bastow: Yeah, absolutely. And for anybody who’s a ProdPad user or interested in ProdPad, I can actually translate this OKR roadmap sandwich into ProdPad terminology, which actually differs because Bruce and I were talking about this last week about how we use the term initiative to mean different things. And this actually indicates how the product world is still settling in on terms. Like the word initiatives, themes, experiments, these are thrown around by product people and product experts and whoever we are and they mean different things to different people, it’s important to make sure that they mean the same thing amongst your people amongst your team.

But I can tell you what they mean in the ProdPad world, which might be helpful for anybody who’s taking a look. So we have OKRs in ProdPad and we have roadmaps. Good to know that they work together. The objectives allow you to check those high-level objectives. And you can have portfolio level and product level. We have KRs, so key results, which are connected to those. And then we have initiatives, which you here call roadmap items or themes. And then connected to those, we have ideas, and I call those-

[00:26:38] Bruce McCarthy: Okay.

[00:26:39] Janna Bastow: … and I call those experiments in my mind, but we call them ideas in ProdPad. And I really call them experiments, ’cause they’re the things that you might try in order to solve the problem or the initiative to, reach that initiative. And one of the reasons why I like taking, I like connecting them that way is that objectives and key results don’t solve the problem by themselves.

You need the initiatives as like that connective tissue.

[00:27:06] Bruce McCarthy: And, you’re absolutely right. And when I teach OKRs, which, that’s become very popular, one of the things that I teach on the first day is, you need the initiatives along with.

[00:27:19] Janna Bastow: Yeah.

[00:27:20] Bruce McCarthy: It’s incomplete without. And what happens if you don’t introduce that third bucket is, people’s initiatives, the things they believe that they should do or the features they believe they should ship, creep into the KRs.

[00:27:39] Janna Bastow: Yes, absolutely.

[00:27:40] Bruce McCarthy: They think of them as, the to-do list, ’cause we all think in terms of to-do lists. We just, it’s human nature, or it’s our training or something, we can’t help ourselves. So there needs to be a place to write your to-do list otherwise, it’s gonna end up in your OKRs.

[00:27:55] Janna Bastow: Yeah, exactly that. So stepping away from product examples, and actually, if then somebody wants to see another product example Bruce has provided another one here, a B2B one but one that steps away from the world of product is in the health space, right? So let’s say your objective is to get more healthy this year, right? Your key result might be something like to lose 15 pounds by the end of the year, or to be able to touch your toes, right? Two things that you might be able to measure, are measurable, specific key results. But you’re not gonna be able to wish your way to these things you’re not going to-

It’s not gonna melt off, you’re not gonna be able to do that if you just lounge around. So your initiatives, the things that you might try to do could involve things like going on a diet or starting a Couch to 5K things that you actually do to make the things happen-

[00:28:49] Bruce McCarthy: Right.

[00:28:49] Janna Bastow: Which you measure with the KRs.

[00:28:51] Bruce McCarthy: What’s great about that analogy is, we’ve all had the experience of deciding to eat healthily or get fit or something like that. And we discover along the way what things work for us and what don’t.

[00:29:03] Janna Bastow: Yeah.

[00:29:06] Bruce McCarthy: I like going, I like, as part of my fitness regimen, I like to go for a walk every day, every, in the afternoon.

And that worked great the first year that I did it right up until we had an ice storm.

And I was like, “Do I really wanna go for a walk right now? No, I really don’t.” So I had to come up with something else. So the list of things to do to get enough exercise in my get fit OKR actually had to change and evolve in order for me to meet the OKRs.

[00:29:41] Janna Bastow: Yeah, that makes a lot of sense. And uh, Kristof has just shared what looks to be a great article in here. Everyone’s raving about it. An article that uses Harry Potter analogies to explain nested OKRs. I will drop that into the link for anybody listening in after this. So it’s in the chat now. We’ll take a look at that afterward. We’ve got some questions coming up in the Q&A section here. So let’s grab one here. Since we’re on this topic right now Fran asks, “How can you prepare a roadmap for a whole year if you’re OKRs are set for just one quarter?”

[00:30:22] Bruce McCarthy: I think there’s a couple of answers to that one. One is, it’s good practice, actually, to set some annual OKRs before you set your quarterly OKRs. A lot of teams don’t do this. And I think it results in incremental thinking. I like to think down the road. In fact, when I teach OKRs, I start with what I call ultimate OKRs.

So if we’re gonna, if we’re gonna talk about what is our vision for this product for what, change we’re gonna make in the world, that might take us two or three years to achieve, right? So let’s describe that future world in the language of OKRs. What are the objectives? How would we know if we had achieved it? What are the KRs? And then, when we’re thinking about this year’s OKRs or this quarter’s OKRs, let’s work backward from there. Let’s say, “All right what, are the things that need to change between here and there?” Maybe some of them are just linear we, in that future world we have 80% market share? All right, how much market share can we get this year or this quarter? Maybe it’s much smaller than that but it’s linear.

But other things are more we need to actually establish a relationship with our first customers. That’s a start. That’s much more concrete, that’s much more actionable, right? So, I think of roadmaps and OKRs as both having those long-term and short-term aspects. And probably, ultimately, they work on similar timeframes. If you are willing to look at them, and in those sorts of levels. I hope that helps.

[00:32:15] Janna Bastow: Yeah, it’s a great answer. Great. And I’m just taking a look at some of the other questions in here. Oh, lots of questions coming through. Salome asked, “Could you talk about a healthy relationship between team-level roadmaps and leadership level or product-level roadmaps and OKRs?”

[00:32:35] Bruce McCarthy: Yeah, so one of the difficult topics to tackle, I don’t know if ProdPad tackles this. We didn’t really address it in the roadmapping book, but there’s definitely an article or something about it that needs to be covered in, what I would call portfolio roadmaps. That is, roadmaps that reflect the overall direction, strategy, et cetera, for a group of products that a company may market or a product line. Think about the retail business, usually in consumer goods, there’s a good, better, best tearing of products that are all put together by the same company, even if they are separate brands. And each of those needs its own separate investment, right?

There are a couple of ways to do that. One is, I would just call the summary method, which is that only the high-level themes from your roadmap are, carried up to the portfolio level, and you have swimlanes one for each one for each product. But that only scales so far, if you have 40 products, you can’t have 40 swimlanes on one slide, right?

So another way to do it is to talk about investments. And that, this is a very internal point of view, but we’re gonna invest 60% of our capacity in products in this category, and 20% in this other and the remaining in this other category. And a good portfolio roadmap of that style includes the vision for the whole product line and how it serves the business objectives again and therefore explains and contextualizes that investment strategy of so many resources against this market opportunity and that one and the other one.

The third style is a market expansion roadmap. We’re gonna go into, here’s our core business today, and here are all the adjacencies that we are pursuing. And here, in that case, what you’re mapping is the expansion of your TAM, Total Addressable Market quarter by quarter or year by year.

So those are just three examples. But it’s all the same philosophy of saying, we have an ultimate destination in mind, we have some objective way of measuring progress and we have a statement of the strategy of what we’re investing in to make that happen.

[00:35:23] Janna Bastow: Yeah, that’s a great breakdown of it. And yeah, in ProdPad, we do support product roadmaps, product line roadmaps, and portfolio roadmaps as a roll-up as well as faces to capture things like investments or market-facing information and things like that. So if anybody wants to check that out, then, by all means, come on by.

We’ve got a question here. In a B2B2C business, set up with a subscription business model, OKRs work fantastically internally, but external communication seeks so-called traditional roadmaps. How do we balance this?

[00:36:06] Bruce McCarthy: In a B2B2C context the external roadmap tends to be more traditional in the sense of features and dates. Is that how you interpret that question?

[00:36:15] Janna Bastow: That’s how I interpreted it. Yeah.

[00:36:20] Bruce McCarthy: Yeah. As one I feel strongly that public-facing roadmaps are a good idea in B2B. There are a lot of companies in B2C that prefer to keep their roadmaps close to the vest because they don’t want to cannibalize existing sales by revealing that version two is coming out next month. Not that everyone doesn’t know when Apple releases iPhones every year, but they still, try to keep a lid on it. So the variation here is that in a B2B2C context, probably the C end of that string is not seeing yours except possibly at the very highest level, very vaguest level of strategic level.

The B2- the B, though in that world is your close partners, who are who you are enabling and empowering to do business with those Cs. And I think that the principles that we’ve described, really fit that step in the B2B2C. Really fit the relationship with the other businesses, because they want to hear from you that you understand their challenges in serving those end customers.

You end up with a product vision statement that is we help this type of business to serve their customers by something that we do really well. And when you put in the problem statements, they’re a mix of the consumer customer problems that you solve, and the problems of the businesses that you serve, as well, in doing, in, in being a profitable business that serves those customers. So it’s, layered, but I, do think it’s very transparent and problem-oriented and OKR oriented for those businesses in the middle of that sandwich.

[00:38:36] Janna Bastow: Okay. That’s a great answer. Yeah, thank you so much. And Ryan asked, “Would you say that you should work on creating OKRs before you focus on the roadmap? What comes first?”

[00:38:48] Bruce McCarthy: Oh, yeah, chicken and egg, right? So let me first say that it is a back and forth iterative process. Every time I do a workshop, where we start building all the components of a roadmap, including the OKRs every time we create one component and then the next one, we, the teams end up almost invariably some percentage of them going back and revising the previous component. So it’s a back and forth iterative process.

I would say if, by roadmap you mean, what are we working on, even the customer problems to solve that the OKRs come first. Because it’s about, what goal are we trying to reach? And therefore, what problems are worth working on and focusing on? And what initiatives should we even consider? Because they are or they are not going to move the needle on what we’ve said are our objectives. So objectives should always come before things to do.

That said, where I really like to start both roadmapping and OKR efforts is with that vision, is with the ultimate goal. I also explain it usually as your highest level objective is to reach that vision of the future that you’ve laid out. If I can cheat a little bit, I still say it’s, OKRs is where you start.

[00:40:30] Janna Bastow: Yeah, I think that makes a lot of sense. You’ve gotta know where it is that you’ve gotta go, where it is that you’re trying to go. I always think about OKRs as the guardrails, right? You’ve gotta be able to set those guardrails first so that people know if they’re going too far that way or too far that way-

Like the bumper lines and-

[00:40:47] Bruce McCarthy: Makes complete sense. How do you answer the question? Do we need to consider this edge case in-

[00:40:53] Janna Bastow: Yeah.

[00:40:53] Bruce McCarthy: … in implementing a feature? It depends on the goal,

[00:40:57] Janna Bastow: yeah. Ryan just said in the chat, “The bowling bumpers.” Now that’s going to be stuck in my head. I’m gonna use that, Ryan. Thank you. And the vision being the goal at the end. What do they call that? The, anyways. I, always see the vision as like the-

[00:41:12] Bruce McCarthy: In bowling?

[00:41:12] Janna Bastow: … the direction … Yeah, the lane. But like the-

[00:41:15] Bruce McCarthy: Yes.

[00:41:15] Janna Bastow: … the area that you’re going down the end and then the bumper lanes, right? Katie asked, “Should you lock in roadmap items for a quarter?”

[00:41:26] Bruce McCarthy: Good question.

[00:41:27] Janna Bastow: … Yeah.

[00:41:28] Bruce McCarthy: So again, it depends on what you mean, by roadmap items. If you mean problems to solve, yeah, probably. And it’s a good idea.

[00:41:35] Janna Bastow: Yes.

[00:41:35] Bruce McCarthy: And then you want to be flexible about the number one thing you’re gonna try to solve that problem, because you’re gonna learn during the quarter which things are working in which things are not working, or at least you should be learning.

But you might, on occasion, learn by implementing a feature and testing it to see if it solves the problem, that “Oh, crap, we’ve defined the problem wrong.” The re- that what we learned … All of a sudden, people don’t use it at all, or they use it in some completely unanticipated way. And we do our research and talk to those users, and find out that we have completely misunderstood something important. In which case, there’s always the occasion for pulling the emergency cord and saying, “We’re on the wrong track, we need to revise the roadmap.”

But I do like the idea of saying “We are dedicating a certain amount of the team’s capacity for a certain time box, a quarter, say, to a problem, and we’re gonna do our best to solve the problem in time.”

[00:42:38] Janna Bastow: Yeah, that makes a lot of sense. Okay. Another great question here from Nicole is, how involved is engineering in the roadmap planning?

[00:42:49] Bruce McCarthy: Ooh, really good question. See, roadmapping, like OKRs, I think is a team sport. I think if, somebody says the product manager goes off and does it in their office or in their home office or their living room by themselves, and then just hands it to the team, that’s doomed to failure.

It’s doomed to failure for two important reasons. One is, you’ve left out a whole bunch of really smart people from a process that’s really important. Why would you not leverage the ideas, the insight, intellectual challenge, and rigor of a debate with your whole team, with engineering with design with data science, even with your testers? I had a really, annoying guy for my very first QA manager as a product manager a thousand years ago, he would poke holes in everything that I came up with.

It seemed like his personality was just like “but what about”, and I found that really annoying until we, I got to like his fifth “what about”, after dismissing all the other ones and said, “Oh, yeah, wait, I didn’t think of that you’re right we need to revise the plan.” Why not make use of, brains like that. He became a good friend and the guy I went to first with all of my crazy hare-brained schemes, because he would, one time out of five, would find a hole that we needed to fix before it became the official plan. So why not do that?

The second really important reason to involve engineering and all the other functions is buy-in. If they don’t have any window into why, or any sense of authorship and ownership of the plan, they’re not gonna be really bought into implementing the plan. I’m vividly remembering a conversation with a young engineering manager who complained about his product manager counterpart, who wanted to engage him in a conversation like this. He said, “Look, if you know what you wanna build, why don’t you just tell me?” And I thought, “Wow, that is really not understanding the healthy relationship that should exist across a team, a squad that owns the success of the customer, and thereby the business.”

I want all brains on deck to think about the problem and the best way to solve it. I don’t like this handoff process of I, I write a bunch of requirements out of my head, I hand it to the designer, they do the wireframes, they hand it to the engineers and they implement it. That’s a recipe for failure in the customer’s eyes and a really slow progression.

[00:45:57] Janna Bastow: Yeah. I’ve seen some real magic happen when you open up the roadmap to the rest of the team to see. Part of the magic of having the problems outlined on the roadmap is that you might have other people come in there and say, “Oh if this is a problem, here’s actually a way that it could be solved. And they start having this really fruitful discussion about how it’s actually not that big of a problem after all, and how it could be solved that much faster. And you get some developer really psyched up about it and is solved two sprints later. Or they actually decide that if you flip it around this way, and put these two together, bam problem solved, and you can do so much more with it.

If you’re trying to make it up yourself, and you’re hiding this stuff away until you think it’s the right order, you’ll actually probably end up solving things in a much less efficient way than if you get-

[00:46:42] Bruce McCarthy: Yeah.

[00:46:42] Janna Bastow: … your technical brains on the solution as well or all your brains.

[00:46:47] Bruce McCarthy: And I’m sympathetic sometimes with engineers or engineering management that is trying to use their resources efficiently and saying, “I want my coders coding. I don’t want them in your stupid meetings, Product Manager.”

[00:47:00] Janna Bastow: Yeah.

[00:47:01] Bruce McCarthy: But I think that is a short-term way of thinking about, results. Yeah, more code will get written more quickly, but will it actually move the needle on your OKRs, on your results? Will it actually solve the problems for the customers? Not as well as if you have everybody involved in the process.

[00:47:23] Janna Bastow: Yeah. So that’s a good take on the engineering side. Arnold had a question in the chat about, how do you reconcile the time difference between the product team, the engineering side, and the rest of the company such as sales? So what he means is, the product team working on initiatives that will have an impact on the n+1 cycle compared to sales, who are making an impact on the current cycle?

[00:47:47] Bruce McCarthy: That’s one of the reasons why I don’t actually like having the revenue number as an OKR. Because it is a lagging indicator. And as you say, the product team can have an effect on it multiple quarters down the road, not right away. It might be an objective at the company level to hit a certain volume by the end of the year.

Although like I said, I put those over onto the side usually and say actually, I have a client who said a brilliant thing. He said, “We have a product line, and it has multiple products in it, and we want to increase our margin on our business as a whole, but I don’t want to set an OKR that says increase the margin. What I want to do is to say, I want to shift the mix of the products that we sell to the more profitable products. So I wanna sell things that are more profitable, differentially to the same customers.” and that will have the effect of moving the needle on margin. But he pointed out correctly, that gives really good direction to the product team.

Okay, so if improving the mix toward more profitable products is the idea, let’s put more investment in those more profitable products and make them attractive, so they’re easier to sell. Let’s have visibility and cross-selling built into the product experience so that the people are using the less profitable products to learn about the more profitable products. In the experience, let’s do what we can to support that because there, there’s a clear statement of strategy in that OKR, rather than just saying, “Oh, let’s increase the sales.” Or, “Let’s increase the margin.”

[00:49:39] Janna Bastow: Yeah, that’s a really good point. And actually, a note on that one thing that I always find interesting with roadmaps is that they’re often filled with things that are designed just to keep the engineering team busy, as opposed to things that make use of sales and marketing and the rest of the team busy, right? Not just to keep them busy, but to, make use of their resources, right?

[00:49:59] Bruce McCarthy: Yeah.

[00:49:59] Janna Bastow: Like the time I talk about experiments and when you even talk about initiatives you know, things that a team should be doing, they shouldn’t just be building new features, or changing the interfaces. They can be things like, let’s get sales to road test this new pricing, let’s get marketing to, Try out this new proposition and see if that works. Because some of the experiments you could run could be game-changing. And don’t involve the engineering team whatsoever. They should be just involved.

[00:50:32] Bruce McCarthy: Could be packaging, or pricing or marketing or documentation. Exactly. This is the Build Trap, Melissa Perri talks about a lot. And I totally agree. OKRs are extremely useful in this situation. Because if you know what the real goals are, then you start to think more broadly and cross-functionally and holistically about what might we do. That’s where the initiatives come from, is, we have the OKRs, what might we do to achieve those goals. And I, worked with this one team they, had an SDK that people could embed in their mobile app. And they weren’t getting a lot of people who downloaded the SDK to actually install it and start seeing the telemetry from their API. And they thought this is a critical point in our funnel, our customer acquisition funnel that’s not working optimally.

And they had a theory about the problem. The theory was that the SDK was too big and bulky and that the process of hooking it up was too complicated for those development teams. And so they wanted to shrink the size of the SDK and make the integration points fewer and easier and more discoverable. And they thought that it would work. So they assigned three developers and a product manager to this for a quarter and said, “Go to it, folks.”

Then they started, at that point, they started talking to customers. And they discovered on a couple of calls, that actually the process of hooking up the … That the size didn’t matter, and that the process was actually pretty simple, as long as someone explained it to you well. And they realized their whole problem was poor documentation. And those three developers and that product manager set about for that quarter to write better doc. When I checked in with them about halfway through the quarter I said, “Are you guys having fun with this project?” And they’re like we’re developers, we’d rather be writing code, but we’re helping the customer and we’re meeting the goal. Customers are super enthusiastic with the early documentation that we have provided so far.” And they were actually psyched to be doing it.

[00:52:51] Janna Bastow: Oh, that’s great. That’s wonderful. There’s a question here from Katie, perhaps a little on the technical side, which is really useful. Where do you put the problems before you pick the ones that you’re focusing on?

[00:53:04] Bruce McCarthy: Oh, good question. So I’m sure ProdPad has a good answer to this. My method, which I think you’ll support, broadly speaking, is, you have a master list of problems to solve somewhere. And you, it goes on longer than the items that are on your roadmap, because some of them are not yet well understood or validated or researched and vetted. So the ones though that you are, that you have enough information on to say they are highly leveraged, they will definitely make a difference for the customer if we solve them, and we think we know how we might approach the problem, those are the ones that are gonna rise to the top of your prioritization matrix and that is gonna get plucked off for the roadmap. Is that how you would do it, Janna?

[00:53:55] Janna Bastow: Yeah that’s a great answer. Yeah, absolutely. And Starr dropped a note in the chat here as well and said, “Candidates.” ProdPad has a concept in the roadmap called candidates where you hold your problems to one side and then you can just drag them into the roadmap when you’re ready. And we’ve got an idea backlog where you keep your experiments or your ideas, and you can drop them onto the roadmap when you’re ready. So got that in place.

[00:54:20] Bruce McCarthy: Product managers are, rather famous before the advent of great tools like ProdPad, of having a spreadsheet somewhere, right?

[00:54:29] Janna Bastow: Yeah. And at the risk of going over, I realized, we’ve got a great question here. Salma has just called us out on this and said, “In the session invite you mentioned that we would learn about what John Doerr got wrong about OKRs.” I’ve totally forgotten to ask this question. We had so many other great questions.

[00:54:43] Bruce McCarthy: Okay.

[00:54:44] Janna Bastow: What did John Doerr get wrong about OKRs?

[00:54:50] Bruce McCarthy: Two things. One, we touched on a little bit already John says correctly in Measure What Matters, “OKRs are the measure of progress.” But then when you get into his examples, a bunch of them are things to do. A bunch of them are ship this feature or hire this person, or it’s the to-do list. And he doesn’t have this third category of initiatives. And so he himself in his examples suffers from this creep of the to-do list into the KRs. And I think it’s misleading.

He even has a weasel word in his explanation of OKRs, where he just as a throwaway says, “Steps in order to achieve the business objective.” And that’s just wrong. And I think if you, if someone were to interview John Doerr now, having worked with, his team has worked with a lot of companies, I think that they have an understanding of that. But in the book, if you’re not careful, you can be misled by some of the canonical examples.

There’s a second one that I think is also important. I think that OKRs work best as a way to align across functions on common objectives. That is in the product, world, product management, engineering, design, data science, testing, et cetera, if we’re all, if we share one set of OKRs for the team that is related to the customer and or the business, then we’re all on the same team, we’re all pushing in the same direction, right? That’s great. And we share those goals. But if you look again, at some of the examples in Measure What Matters, they are very departmental and functional.

His first table for how OKRs cascade is about an American football team winning the Super Bowl and filling the stands. And it breaks everything down in terms of which team is working on which objective and which OKRs right down to the defensive coach. And I think that is again, misleading and unrealistic. If your marketing team has different objectives than your sales team what motivates them to work together to acquire customers?

I worked with this one, just a quick story. I worked with this one team, where they were really proud of themselves for having set up goals for everybody. And the product team had an objective. And they had a bonus tied to this objective to ship new features. And the engineering team had an objective to ship always on time. And the testing team had an objective to file more bugs. And they all had bonuses tied to these objectives. And as soon as the testing team started generating a zillion bugs in order to get their bonus, the development team kept closing all of them as not a bug. Because, arguably, some of them weren’t, but they were also closing things that clearly were a bug as bugs because it would slow them down and they would have to work on them and it risked their ship date. And the, they also kept saying no to all the product features. “Oh, it’s gonna make us late, we can’t do that.”

So all three of them were completely at odds until we reset the objectives to be team objectives. A team in the sense of a product, cross functional product team that incorporates all of those functions.

[00:58:40] Janna Bastow: Wonderful.

[00:58:40] Bruce McCarthy: So those are the two things, I think John Doerr got wrong. A much better book if you’re looking for a book on OKRs, Christina Wodtke’s Radical Focus she gets it right. And it’s a super easy read.

[00:58:57] Janna Bastow: yep, Thank you so much for, tackling that one. And thank you so much for sticking with us over the hour. You’ve been absolutely wonderful. It’s been a great session. You’ve everyone, you’ve given us some great food for thought and some great questions here and Bruce, thank you so much for taking the time to chat with us here today.

[00:59:16] Bruce McCarthy: Yeah. [inaudible 01:15:32].

[00:59:18] Janna Bastow: There were some questions that we didn’t get to today. So I’ve noted some of these down and hopefully, we’ll get a chance to get to them in due course. Definitely subscribe to Bruce’s newsletter. He does is it called,

[00:59:33] Bruce McCarthy: Called a Nano-letter.

[00:59:34] Janna Bastow: Nano-letter, yeah.

[00:59:35] Bruce McCarthy: Really, short. Like just, this the one screen on your phone?

[00:59:40] Janna Bastow: Yeah. Like one thing on.

[00:59:43] Bruce McCarthy: One Thing on Product Culture, and it’s always about something that this audience I think would find very interesting. If you go to productculture.com, you can subscribe there.

[00:59:53] Janna Bastow: Yep. And you will be getting this recording in due time. So keep an eye out for that in the coming days. And keep an eye out for our next webinar. There’ll be another one same place next month. We will announce that in the coming days as well. So thank you all and thank you so much, Bruce take care. Have a wonderful day.

[01:00:16] Bruce McCarthy: Awesome. Thanks for having me.

[01:00:18] Janna Bastow: All right, thanks. Bye.

Watch more of our Product Expert webinars

How to Build and Manage AI Products and Features

Watch ProdPad Co-Founder and CTO, Simon Cast, for a deep dive into the practicalities of building AI products and features, whether you’re enhancing an existing product or launching something entirely new.

How to Master the Modern Product Manager Hiring Process with Lewis C. Lin

Watch Lewis C. Lin, renowned interview coach and author, and host Janna Bastow as they unpack key changes in PM hiring and offer frameworks, insights, and tactical advice for navigating it all.

How Radical Product Thinking Can Transform the Way You Build Products

Watch Radhika Dutt, Founder of Radical Product Thinking, and host, Janna Bastow, CEO of ProdPad as they share how to break free from iteration cycles and focus on vision-driven product development.

How to Run a Product Launch: A GTM Guide for Product Managers

Watch Julie Hammers, Head of Product at ProdPad, and Megan Saker, Chief Marketing Officer, as they break down exactly how to lead the GTM process with confidence and run a successful launch.