The Psychology Behind Building Products: Psych-Savvy Product Management For Truly Human Technology

Your average product management team is fully behind the concept of user-centric design and development.

But what about people-centric products? What we still sometimes fail to remember is that we are building for human beings with deeply human desires, flaws, motivations and limitations that don’t stop when they become users of our products. Psychological principles become increasingly important when we consider customers and users in this way, but what is the role of psychology, neuroscience or social behavioral study in real product management? How can it be harnessed to build better products?

In this article we take a look at 3 key principles of a more psych-savvy approach to designing and building products.

Understanding customers is about understanding people

One of the most valuable but perhaps most abstract changes that psychology brings to product is a different way of thinking about your users. At this year’s Mind the Product conference, Interaction and Experience Research Director for Intel – Genevieve Bell – shared with us an understanding of human behavior that could transform a product manager’s typical approach to their users. She highlighted that while we’re tempted to believe that changes in technology reflect changes in us as human beings, what makes us human in fact changes very slowly.

An appreciation of this bigger picture can make us better product managers. Genevieve herself – an anthropologist – is an example of Intel’s appreciation for a different outlook on understanding customers. And she’s not the only one; from psychology-led design consultancy Behaviour, to psychology graduate and founder of Fitbit Tim Roberts, many more with human behavior in their blood are turning their training to building and making products.

Don Norman even calls for changes to design education to better equip designers for the social experiences they are creating:

“In the early days of industrial design, the work was primarily focused upon physical products. Today, however, designers work on organizational structure and social problems, on interaction, service, and experience design. Many problems involve complex social and political issues. As a result, designers have become applied behavioral scientists, but they are woefully under-educated for the task.”

Of course, this doesn’t mean that every product manager needs to rush off back to school to get their psychology degree. But perhaps reading a book or article here or there, re-educating your team to consider the humanness of your customers, could give you the perspective you need to take your products from average to awesome.

Building sticky products is about habit forming

Getting into the heads of your users can be applied much more directly than a general approach to product, however. One of the industry’s leading thought leaders on the intersection between technology, business and psychology – Nir Eyal – also spoke to us at this year’s Mind the Product on the power of habit forming in your technology products.

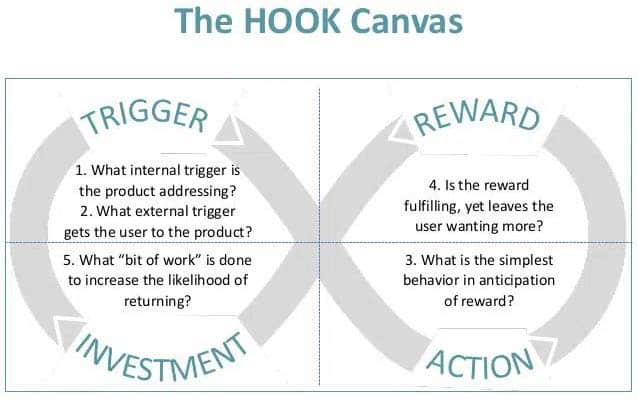

“The hook is an experience designed to connect the user’s problem to your solution, with enough frequency to form habits.”

How Facebook, Twitter and other major technologies have exploded into our lives in the past few years is no pure coincidence. In theory, all product managers can use the science of habit forming to figure out how to trigger desired behavior in their users. Of course, that’s no simple task, but a little part of the brain called the nucleus accumbens can help to give us a head start. This stimulates the stress of desire, and it is these cravings that move us to action. Moving users to strive for rewards from your product, which might take the form of social, resource, mastery, or investment-based rewards can help you encourage them to come back again and again.

An example of this habits-based approach comes from Behaviour, who worked with psychologists at University College London to build behavioral insight into the design of an app for breast cancer charity CoppaFeel. Elements such as taking a pledge when starting the app to encourage a long-term commitment, and data on how many other users have ‘copped a feel’ for social proof, were developed to encourage young women to form a habit.

Perhaps an element of your product could be reimagined to encourage more habit-based behavior in the hunt for one of these basic human rewards.

Good products treat customers as humans at every step

As businesses we are sometimes guilty of investing all of our empathy for customers into the initial development of our products or marketing, but forgetting that these people face the same challenges when they’re using our products too. Kathy Sierra delivered a very strong message at Mind the Product, urging product people not to trade personas for stock photo images of their users after the sale.

When we’re trying to build great products it’s not just about motivating users, but keeping them on track in face of lagging willpower. So how can we overcome this derailment of our users? An important psychological concept to be mindful of when assessing your entire customer experience is cognitive leaks. Don’t suck away your users cognitive power when they’re trying to use your product; instead limit choice, provide clear instructions and support and offer clean feedback so your users’ brains can rest assured you’ve got it covered.

Don’t forget that your users never stop being the very human people that they are, and account for that at every stage of their customer journey.

2 thoughts on "The Psychology Behind Building Products: Psych-Savvy Product Management For Truly Human Technology"

Comments are closed.

It’s all about the psychology. Marketers, product managers, and user experience designers like to think that, if they have a “user or consumer focus”, that quality product decisions naturally result. The flaw is that you have to understand human behavior beyond your own personal intuitions to make any truly informed decisions.

Just because a marketer herself has experience as a consumer doesn’t mean she is an expert on consumer behavior. (Take the example of naming a product or a company.) Just because a UX designer has herself experienced many different products and interfaces doesn’t mean she is an expert on user behavior. The actual science of how consumers and users respond to messages, imagery, and interfaces frequently contradicts what our intuitions would have us believe.

Agree with Roger, and one of ways to work-around that is to think in terms of specific personas.